![]() We don’t usually learn about the physics of squishy things. Physics textbooks are filled with solid objects such as incompressible blocks, inclined planes and inelastic strings. This is the rigid world that obeys Newton’s laws of motion. Here, squishiness is an exception and drag is routinely ignored. The only elastic object around is a spring, and it is perfectly elastic. It will never bend too far and lose its shape. But any child who has played vigorously with a Slinky has stretched past the limits of this Newtonian world.

We don’t usually learn about the physics of squishy things. Physics textbooks are filled with solid objects such as incompressible blocks, inclined planes and inelastic strings. This is the rigid world that obeys Newton’s laws of motion. Here, squishiness is an exception and drag is routinely ignored. The only elastic object around is a spring, and it is perfectly elastic. It will never bend too far and lose its shape. But any child who has played vigorously with a Slinky has stretched past the limits of this Newtonian world.

Whereas the rigid universe is notable for its strict adherence to a few basic principles, the squishy universe is a different beast altogether.

I was recently out paddling, and noticed that as you move the paddle through water, tiny whirlpools begin to develop along its sides. The whirlpools grow in size, become self-sustaining, and break off and float away. Eventually they die out, as they lose their energy to the fluid around them.

You could also watch the spirals and vortices created by rising smoke. Or notice the strange shapes made by the wind as it sweeps through the clouds. It’s as if fluids have a life of their own, often wondrous and beautiful, and other times surprising and counter-intuitive.

But the motion of fluids is notoriously hard to predict. It’s so difficult that if you can solve the equations of fluid flow, there are people willing to offer you a million dollars. The difficulty comes from a mathematical property of the equations known as non-linearity. Simply put, a non-linear system is one where a small change can lead to a large effect. The same thing that makes these equations difficult to solve is also what makes fluids surprising and interesting. It’s why the weather is so hard to predict – tiny changes in local temperatures and pressures can have a large effect.

At this point, most reasonable people would throw their arms up in despair. But physicists are an unreasonably persistent bunch, and when faced with an equation that they can’t solve, they try to get some insight by looking at what happens at extremes. For example, thick and syrupy fluids like glycerine behave in a surprisingly orderly fashion. Take a look at this video (watch through to the end, it’s worth it).

I bet you’ve never seen a fluid do that before. So what’s going on here? And what does this have to do with swimming sperm?

Let’s take a step back. Picture a flowing river. If there is an obstruction to the water’s path, like a rock jutting out of the surface, the water will move around it and swirl back upstream. Behind the rock, the water remains relatively calm. What you get is a spot on a moving river where the water is remarkably still. These calm spots are called eddies, and kayakers treat them as parking spots on the river.

Let’s take a step back. Picture a flowing river. If there is an obstruction to the water’s path, like a rock jutting out of the surface, the water will move around it and swirl back upstream. Behind the rock, the water remains relatively calm. What you get is a spot on a moving river where the water is remarkably still. These calm spots are called eddies, and kayakers treat them as parking spots on the river.

But fluids don’t always behave like this. If you replace all the water in a river with a viscous fluid like glycerine, there won’t be any eddies. The syrup will simply follow the contours of the rock and smoothly flow around it.

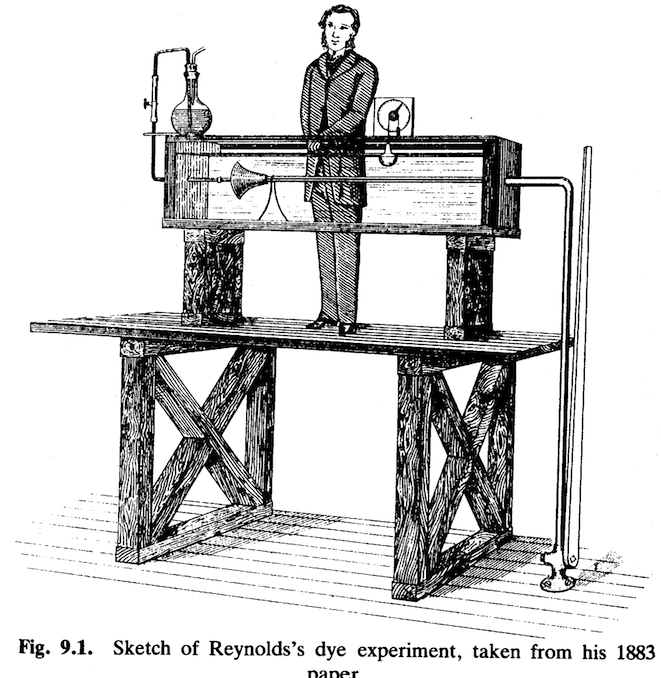

In one case we have smooth, orderly flow, and in the other case we have eddies and turbulent flow. The question arises, is there any way to know what kind of flow will result in a given situation? This question was answered by the physicist Osborne Reynolds in 1883, and he answered it in style.

Here is Reynolds’ elegant experiment. He sent fluid flowing through a thin pipe (analogous to the river), and injected colored dye in a small section of the flow. He watched the dye flow down the tube, and could plainly see whether the flow was smooth or disorderly. By tweaking the parameters in this experiment, he was able to discover the conditions that ensure an orderly flow.

What he found is that there is one simple, magic number that can predict what is going to happen. It neatly ties together all the different physical quantities involved. It’s been named Reynolds number (Re for short), and is given by

These are all quantities that you can directly measure. The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of how slowly it flows. Thick and syrupy fluids like honey and corn syrup have a high viscosity, gases like air have a very low viscosity, and water is somewhere in between. The length in the above equation is a length that describes the object that you are studying (say the width of the rock). Reynolds used the diameter of the pipe. And the speed is that of the fluid.

The Reynolds number has the nice property of being dimensionless, meaning that the number is the same in whatever system of units you choose to measure the above quantities (dimension-full quantities are things like speed, which you could measure in km/h or mph). What Reynolds found is that as this number exceeds 2000, you suddenly get turbulent flow. In fact, this week’s issue of Science magazine mentions a new experiment that verifies this surprising result, and puts the turning point at Re = 2040. (The specifics of this number has to do with a fluid moving through a cylindrical tube with smooth walls. In a different situations, the number will change, but the principle is the same. There is a sudden jump from order to turbulence.)

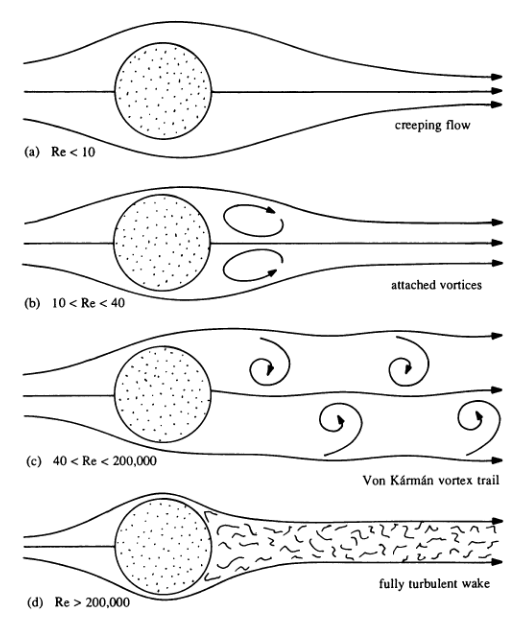

The above figure gives you an idea of what happens as you increase Reynolds number. Here’s an analogy. The low Reynolds number world is like a collectivist ideal, where water moves along uniformly like soldiers marching in step. The high Reynolds number world is the individualist nightmare, where everyone looks out for themselves. Think of a march versus a mob.

We can arrive at this number from another route. There are two fundamentally different type of forces that act on an object immersed in a fluid. The first kind are inertial forces. This is like the push you give to the water when you take a stroke while swimming. Inertia is what allows water particles to keep moving undisturbed. On the other hand, you have viscous forces which measure the tendency for the fluid to smooth out any irregularities. To use the above analogy, inertial forces reflect the individuality of bits of fluid, and viscous forces are like a communist government enforcing conformity. And when you take the ratio of these forces, you get back the Reynolds number.

This number is of immense importance to aeronautical engineers and to biologists interested in locomotion.

Let’s say you want to simulate the effect of wind on a new wing design. You build a scale model in the lab that is one tenth the size of the actual wing.

But remember how the Reynolds number is defined.

If you shrink the size of the wing by a factor of 10, you have to increase the windspeed by the same amount in order to keep the number fixed. The key point is that systems with the same Reynolds number have essentially the same nature of flow. If you didn’t account for this, your wing would be quite a disaster.

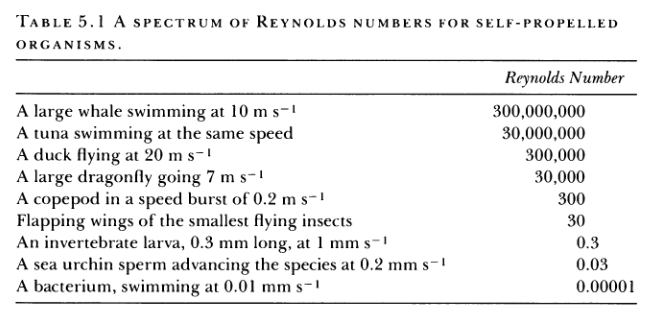

How would a biologist use this idea? Well, nature presents us with organisms that cover an incredible range of sizes, from the tiniest microbes to the blue whales. Here is a table of Reynolds numbers across this range.

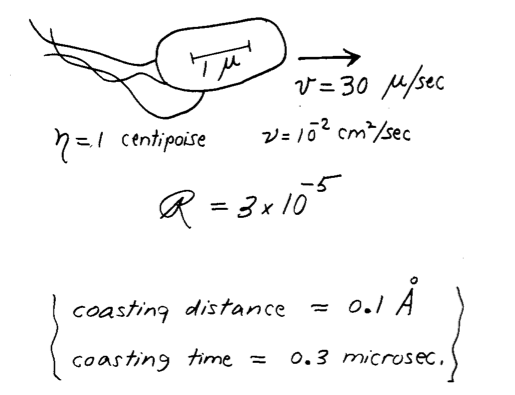

The list covers 14 orders of magnitude. A whale swims at a huge Reynolds number. This means that inertial forces completely dominate. If it flaps its tail once, it can coast ahead for an incredible distance. Bacteria live at the other extreme. In a delightful paper entitled Life at low Reynolds number, the physicist Edward Purcell calculated that if you a push a bacteria and then let go, it will coast for a distance equal to one tenth the diameter of a hydrogen atom before coming to a stop. And it will do this in 3 millionths of a second. Bacteria clearly inhabit a world where inertia is utterly irrelevant.

Eels and sperms may look similar, but their method of moving is very different, as their Reynolds numbers are far apart. In fact, we can now answer the question, what would it feel like to swim like a sperm or a bacteria? To do this, you have to somehow get down to their Reynolds number. We can’t change our size, but we can shrink our Reynolds number by swimming in a very viscous fluid. Purcell estimated that you would have to submerge yourself in a swimming pool full of molasses, and move your arms at the speed of the hands of a clock. (Don’t try this at home. Swimming in molasses is not a good idea.) Under these conditions, if you managed to cover a few meters in a few weeks, then you qualify as a low Reynolds number swimmer.

This clearly isn’t a hospitable environment for denizens of our Middle World. But yet this is the scale of the task that microbes face simply to get around.

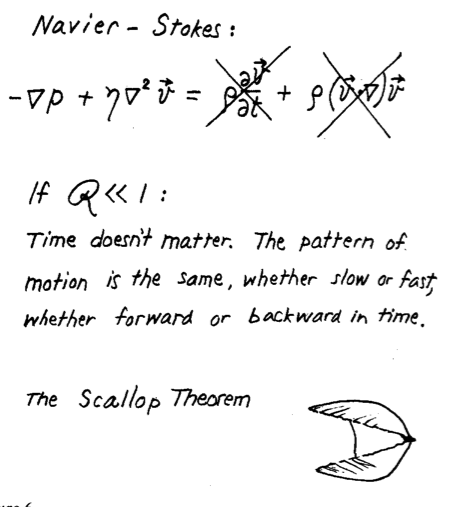

Except, it’s even harder. Remember the youtube video of the colored dye swirling in the glycerine? The reason that the colors come back to where they start is because at low Reynolds number, flow is reversible. Because inertial forces are so small, certain terms drop out of the complicated fluid flow equations. The equations simplify considerably, and not only are they now solvable, they don’t depend on time any more. If you took the youtube video and played it backwards, you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

But this reversibility has a surprising consequence. It means that anything that swims using a repeating flapping motion can’t get anywhere. If it moves forward in one stroke, the other stroke will bring it right back to where it started. Scallops swim by opening their jaws and snapping it shut. In low Reynolds number, scallops can’t get anywhere.

Don’t believe me? See it for yourself. Here’s a rubber band powered toy that paddles forward when in water.

Woohoo! Look at it go. Now, take the same toy and place it in a vat of viscous corn syrup.

The reversibility of the flow ensures that the boat can’t make any progress.

So how, then, do microbes manage to get anywhere? Well, many don’t bother swimming at all, they just let the food drift to them. This is somewhat like a lazy cow that waits for the grass under its mouth to to grow back. But many microbes do swim, and they make use of remarkable adaptations to get around in an environment that is entirely alien to us.

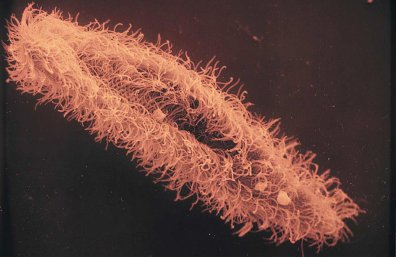

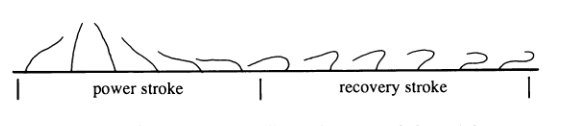

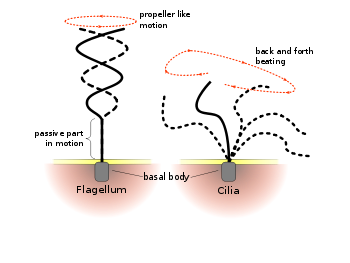

One trick they can use is to deform the shape of their paddle. By cleverly contorting the paddle create more drag on the power stroke than on the recovery stroke, single cell organisms like paramecia break the symmetry of their stroke and thus elude the scallop conundrum. Indeed, this is how the flapping structures known as cilia thrust a cell forward: they flex.

There is an even more ingenious solution that has been hit upon by bacteria, sperm and other cells. Rather than having a cilia, which is essentially a flexible paddle, these cells adopt a different strategy: they use a corkscrew for a propeller. Just as a corkscrew used on a wine bottle converts winding motion into motion along its axis, these organisms spin their helical tails (flagellum) to push themselves forward.

But don’t expect to see human swimmers doing ‘the corkscrew’ anytime soon. This strategy works only at low Reynolds number, where water ‘feels’ as thick as cork, so you can push against it effectively.

And here’s proof. Whereas our rubber band powered stiff paddle couldn’t make any headway in the corn syrup, take a look at what happens if you instead have a helical propeller.

It winds its way into the fluid and inches forwards.

Motion in this viscous world is counter-intuitive and puzzling. By applying science, we can imagine what it must feel like to be very small. And we can work out how to build tiny ships in such a world. But evolution has beaten us to the punchline, and microorganisms have evolved intricate and wonderful structures that pulsate rhythmically and take advantage of the quirks of physics at this scale.

References

Purcell, E. (1977). Life at low Reynolds number American Journal of Physics, 45 (1) DOI: 10.1119/1.10903

Avila K, Moxey D, de Lozar A, Avila M, Barkley D, & Hof B (2011). The onset of turbulence in pipe flow. Science (New York, N.Y.), 333 (6039), 192-6 PMID: 21737736

Reynolds, O. (1883). An Experimental Investigation of the Circumstances Which Determine Whether the Motion of Water Shall Be Direct or Sinuous, and of the Law of Resistance in Parallel Channels. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 35 (224-226), 84-99 DOI: 10.1098/rspl.1883.0018

In addition to the above papers, I learnt a lot about this subject from the following excellent book, from which many of the figures in this post are taken:

Life in moving fluids: the physical biology of flow by Steven Vogel (1996)

The theme of this post came from reading a following wonderful out-of-print book that I discovered in the basement of Strand bookstore in NYC:

On Size and Life (Scientific American Library) (1983)

Image Credits

Figures from the cited papers or from Life in moving fluids by Steven Vogel are attributed in place.

Cartoon of eddies was lifted from Whitewater kayaking: the ultimate guide by Ken Whiting & Kevin Varette

An airfoil wing in a wind tunnel courtesy NASA Langley Research Center

Cilia on a Paramecium courtesy Yellow Tang Moodle

Difference of beating pattern of flagellum and cilia courtesy Wikimedia Commons