![]() Bacteria have busy social lives. You might get a glimpse of this the next time you take a shower. The slimy discolored patches that form on bath tiles and on the inside of shower curtains are the mega-cities of the bacterial world. If you zoom into these patches of grime, you’ll find bustling microcosms that are teeming with life at a different scale.

Bacteria have busy social lives. You might get a glimpse of this the next time you take a shower. The slimy discolored patches that form on bath tiles and on the inside of shower curtains are the mega-cities of the bacterial world. If you zoom into these patches of grime, you’ll find bustling microcosms that are teeming with life at a different scale.

That we can see these microbial communities with our naked eye is testament to the scale of their achievement. Perhaps the most spectacular examples are the giant mats of bacteria that lend life to the Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park. These macroscopic structures are just as impressive as our cities that are visible from outer space. Microbes have colonized practically all moist surfaces on earth, from the inside of our mouths (they’re responsible for dental plaque) to hot vents at the bottom of the ocean. And it all started from small beginnings.

The first wave of bacterial settlers that arrived on your shower curtain were few and far apart. They would try to hold on using the molecular adhesion between themselves and the shower curtain. Those that couldn’t get a grip were flushed down the drain plug.

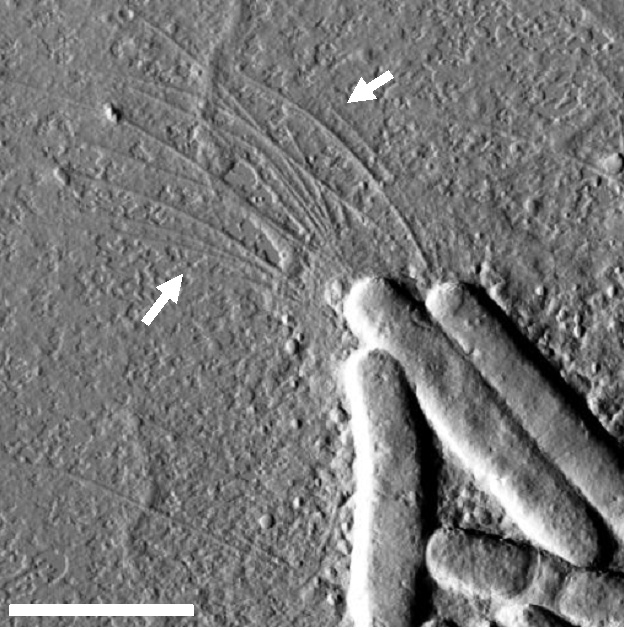

Bacteria have an adaptation that serves them well in such tricky situations. It’s a sort of multi-purpose prong, technically known as a type IV pilus (plural: pili). These wonderful filament-like structures extend out from the bacteria, and grab on to the surface like a suction cup on a bathroom tile. What happens next is straight out of science fiction.

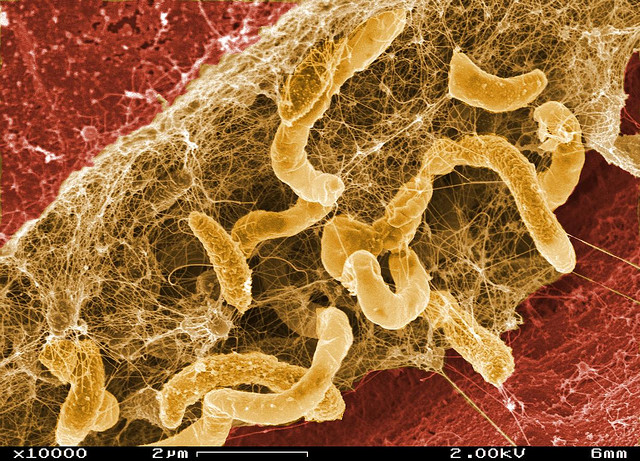

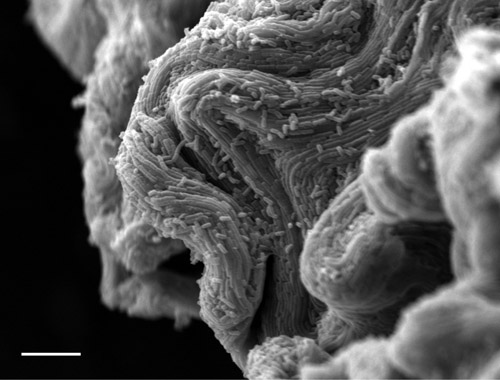

Once these settlers have their ‘feet’ firmly planted on the ground, the next step is to build a home. They begin to excrete a polymer substance, forming a grid that locks them into place. Many different microbes can co-inhabit these homes, from bacteria and archaea to protozoa, fungi and algae. Each species performs a specialized metabolic function, neatly occupying a niche in this city. Together these interlocked communities, or biofilms, are the beginnings of a thriving multicultural microbial civilization.

Continue reading Bacteria use slingshots to slice through slime